Your next homework assignment has been hanging around in the Assignments tab since the afternoon. It’s due Wednesday September 10th at the beginning of class. Very smooth.

If you’re an art critic and you want to become famous, first of all you need to slow down a second because, as Anton Ego notes in Ratatouille, “in the grand scheme of things, the average piece of junk is probably more meaningful than [your] criticism designating it so“. If you look hard at yourself in the mirror and the itch remains, then what you need to do is find some unknown homie or homette (or group thereof) who is killing the game in new and exciting ways, start the hype locomotive and ride it all the way to Fametown, choo choo. You’ll be forever known as the critic who championed this great artist when he was just a neckbearded nobody weaving tapestries in his loft. (In this scenario your discovery is successful in bringing back tapestries as a thing people care about. Just go with it.)

Now, suppose you can’t find any such underground homies. What then? Well, look around for existing homies whose lives are dope and who are doing dope stuff. Found some? Okay, is there a name for what they are doing? No? You see where I’m going with this, right? Come up with one, ya goon. This is what Peter Schjeldahl of The New Yorker attempted this week with an online piece proposing the term “Stunt art” for the often illegal works and actions that commandeer public spaces for displays of daring and disruption. Schjeldahl’s immediate impetus for the piece was the recent nocturnal replacement, by two German artists, of the American flags atop the Brooklyn Bridge with bleached-white versions of same.

Whether Schjeldahl’s term – or, indeed, the art it describes – will endure remains to be seen. In any case, I have to deduct some props from Big Pete (out of my initial allocation of 63) for the straightforwardness of the name. He earns them back, though, with a savvy explication of the milieu in which Stunt art has arisen. In his view, so-called Stuntists, frustrated with a rigidly institutional contemporary art world, seek a more direct conduit for their work — one that can reach an audience whose cultural taste is more Bazinga than Basel. Schjeldahl, in a bold bid for prop recovery, proposes a graceful analogy for the role of the movement within the art scene: “Stuntism is to art as weeds are to horticulture: plants in the wrong place. Authorities, social or botanical, define the wrongness, which becomes more arbitrary the more you think about it. Some weeds are as lovely as tulips.” You know know what he’s talking about dude! Hells yeah — weed culture! Whatta stony baloney. Take the props back, Pete. Take all the props, and take this tub of Haägen-Dazs Bourbon Pecan Praline, too. You’ve earned it

Of course, tension between critics and the art world power structure is nothing new. Louis Vauxcelles, a leading art critic in the beginning of the 20th century, was as averse as any avant-gardiste to the academic style and philosophy of the Paris Salon. This alone does not earn him props, however; the Impressionist had long since turned the staid art world on its head and given it a killer nature wedgie (that’s like a regular wedgie but you throw in like burrs and brambles and other nature stuff too). Despite his anti-conventionalist bent, Vauxcelles was not particularly keen on Picasso, Matisse, and the other young revolutionaries plowing their painterly path through the Paris art scene. Remarkably, it was this distaste for the men who would become his era’s leading luminaries that ended up ensuring Vauxcelles’s position in the annals of art history – not for his myopia but for for his role in coining two of the most famous terms of 20th century art: Fauvism and Cubism. Tellingly, each appellation arose not from a deliberate attempt to define a movement (à la Schjeldahl) but from incidental remarks that resonated and endured.

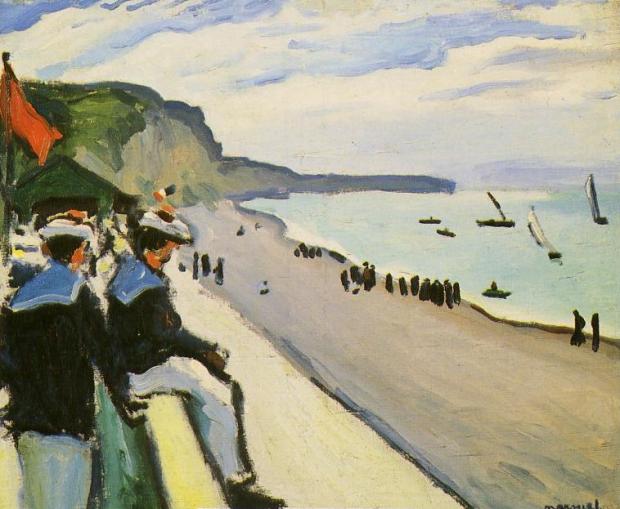

This painting was among those exhibited in the now-famous 1905 Salon d’Automne in Paris. Note the abstracted forms, the loose, wild brush strokes; note, too, the vivid colors: a face of yellows and greens not normally seen in the absence of jaundice or seasickness*. Vauxcelles was not amused. Speaking with the artist in a salon room that a classically inspired sculpture by Albert Marque** shared with several exuberant, wildly colored paintings by Matisse and his confrères, Vauxcelles referred to the more conventional work as “Donatello parmi les fauves” (“Donatello amongst the wild beasts”). He liked the phrase so much he repeated it (approximately) in his written review of the exhibition days later, leading Matisse to brand him an outfit repeater (metaphorically speaking, of course). Not until Kate Middleton was seen wearing the same dress on more than one occasion did Vauxcelles’s reputation recover.

Nailing down the exact wording of the original French of that crucial phrase took some legwork. Various sources have it as above, as “Donatello au milieu des fauves”, or as “Donatello chez les fauves”. Rigorous sleuthing brought me to Vauxcelle’s original article from the newspaper Gil Blas, where in the section describing Salle VII (Room 7) of the exhibition he writes “Au centre de la salle, un torse d’enfant et un petit buste en marbre, d’Albert Marque, qui modèle avec une science délicate. La candeur de ces bustes surprend au milieu de l’orgie des tons purs : Donatello chez les fauves…” [“At the center of the room, a child’s torso and a small marble bust by Albert Marque, who sculpts with a delicate touch. The candor of his bustes surprises amongst the orgy of pure tones: Donatello in the wild beasts’ home.”]***

Georges Braque – Houses at L’Estaque (1908)

Vauxcelles’s claim to coinage of “Cubism” is not quite as strong, but you know he still tried to use it to impress the ladies, the bastard. Probably worked, too. Heck, I’d’ve gone for it. Cubism, man! You know Louis picked up some residual magnetism from Picasso. (Residual magnetism is a thing, right?) Anyway, Matisse apparently was the first to describe George Braque’s seminal 1908 works from L’Estaque in the south of France as being composed of “petits cubes”, and art dealer Leonce Rosenberg claimed to have heard him use the word Cubisme in the same conversations. Vauxcelles, who didn’t have the moral principles of an Anton Ego or a Roger Ebert, echoed the sentiment in a review of Braque’s work in which he wrote of Braque’s “reducing everything […] to geometric schema, to cubes.” The following year, drunk with power, he riffed on the idea, calling Braque’s offerings at the Salon des Indépendants “bizarreries cubiques” [“cubic oddities”]. The Salon of 1911 advertised “Cubist” work by Albert Griezes, Jean Metzinger, and others^; this was the public’s introduction to the term. The next year, Griezes and Metzinger published Du “Cubisme”, further ensuring the term’s permanence.

In 1911, Vauxcelles, undoubtedly rather impressed with himself as a master of coin after the quick spread of “Fauvism” and “Cubism” (the terms, that is), tried to make “Tubism” happen as a descriptor for the refracted, cylindrical style of Fernand Léger.

Fernand Léger – Nudes in the Forest (1910)

It’s fairly clever, and (more importantly) aptly describes Léger’s work, which is among the most distinctive and recognizable in 20th-century art. Nevertheless, it failed to catch on as widely as did Vauxcelles’s other coinages, for several reasons. Its conscious conception was an impediment, especially since Vauxcelles did not intend it as a compliment. “Fauvism” and “Cubism” are nomenclature born of derision, but they arose upon the coöption of the derisive terms by the artists; “Tubism” couldn’t be coöpted in the same way because it was presented by Vauxcelles fully realized, unlike the fauves and cubes of his earlier articles^^.

Armchair sociological investigation aside, the main reason most people have never heard of Tubism is that few, if any, artists joined Léger in exploration of the form, which is a shame, because he produced great work, drawing on the formal innovations of Cubism and the modernist preoccupations of Futurism to forge his own unmistakable aesthetic.

Fernand Léger – The Card Players (1917)

With just one major artist, Tubism was not really a movement, and so did not really require a name (though “Tubist” is an adjective far superior to “Légerian”).

* Apart from a few masters of penetrative realism like Rembrandt and Velázquez, I generally prefer this type of portraiture. I find the exotic colors more evocative and, perhaps ironically, more deeply representational. By bringing to prominence the subtle hues that can be present but not obvious, or even necessarily visible, to the undiscerning eye, the artist forces the viewer to see more intensely, to consider how much visual information he or she is taking in while looking at a face, and of what components that information is composed. Earlier this week I finally made it to MoMA PS1 to see the Maria Lassnig exhibition (just in time; it closes September 7th). Most of the portraiture on display showcased expressive brush strokes and bold color, but she could also be srsly sombre when she felt like it. Check the versatility:

** Incidentally, Albert Marque was not himself a Fauvist, but fellow-Parisian Albert Marquet, three years his junior, was; in fact, Marquet had lived with Matisse while they were students, and the two remained friends throughout their lifetimes. Marquet never achieved anywhere near the renown of his old chum, but he threw down some fairly dope canvasses in his day

Albert Marquet – The Beach of Fécamp (1906)

Pretty clearly not the work of a genius (the posters one is tight tho), but he does help you appreciate Matisse’s brilliance, which, despite the riotous, attention-grabbing color can sometimes be disarmingly subtle, as in this work on view at the MoMA:

*** Interestingly, though this sentence is the one most often cited as the origin of “Fauvism” (and it surely is), Vauxcelles begins his analysis of Salle VII with a discussion of Matisse in which he writes “Il a du courage, car son envoi — il le sait, de reste — aura le sort d’une vierge chrétienne livrée aux fauves du Cirque.” [“He has courage, for his submission — he knows, moreover — will have the fate of a Christian virgin delivered to the beasts of the Circus.”] I suppose these circus beasts are of a different ilk than the ones that surround Marque’s statues.

^ Though not Braque nor Picasso, as they both had exclusive, proto-360º deals with the legendary art dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler whereby he guaranteed them an income in exchange for the right to buy all their work. He also made them play mahjongg with him and his buddy Rufus, which Picasso hated but Braque kind of enjoyed, except when Rufus ate a salami sandwich at the table, which Braque thought was pretty rude [Ed. – There’s no way that last part is true]

^^ It’s like how when I was in middle school and there was this guy Leo Vassals who liked to make fun of me and my friends. We used to sit near each other in English class and this girl Alba Márquez, who was really a classic beauty, sat sort of in the middle of us, and one day Leo said that she was like a Madonna amongst hippopotamuses. Rather than getting bummed out, we turned the tables on Leo by calling ourselves the Hippos, thus reclaiming the term for ourselves. Later that year Leo started telling everyone that these brothers Brago and Pischmasso who wore square-rimmed glasses looked like they had windows on their faces. Next thing you know they’re going around calling themselves the Black Windows (Like a play on Black Widow? Idk, we were like 13 so it was clever to us. I still think it’s pretty good.) and they’re the coolest dudes in school. Funny how history repeats itself like that, from the beginning of one century to the beginning of the next, from Paris to Poughkeepsie. The parallels continue: when Leo set his sights on the clique of skinny kids (most of our school’s cliques were based on shape — conclude from “Hippos” what you will) by trying to get everyone to call them the Bucatini Boys, they didn’t embrace the name because that was exactly how the insult was presented — as a name for them. In this case, though, unlike Tubism, the Bucatini Boys nickname stuck, because it was hilarious. Everyone loved it (except the skinny kids, obviously, but whatever).